Beyond the blacklist

Bouncing back from cancel culture in South Korea.

by Katie Tsang

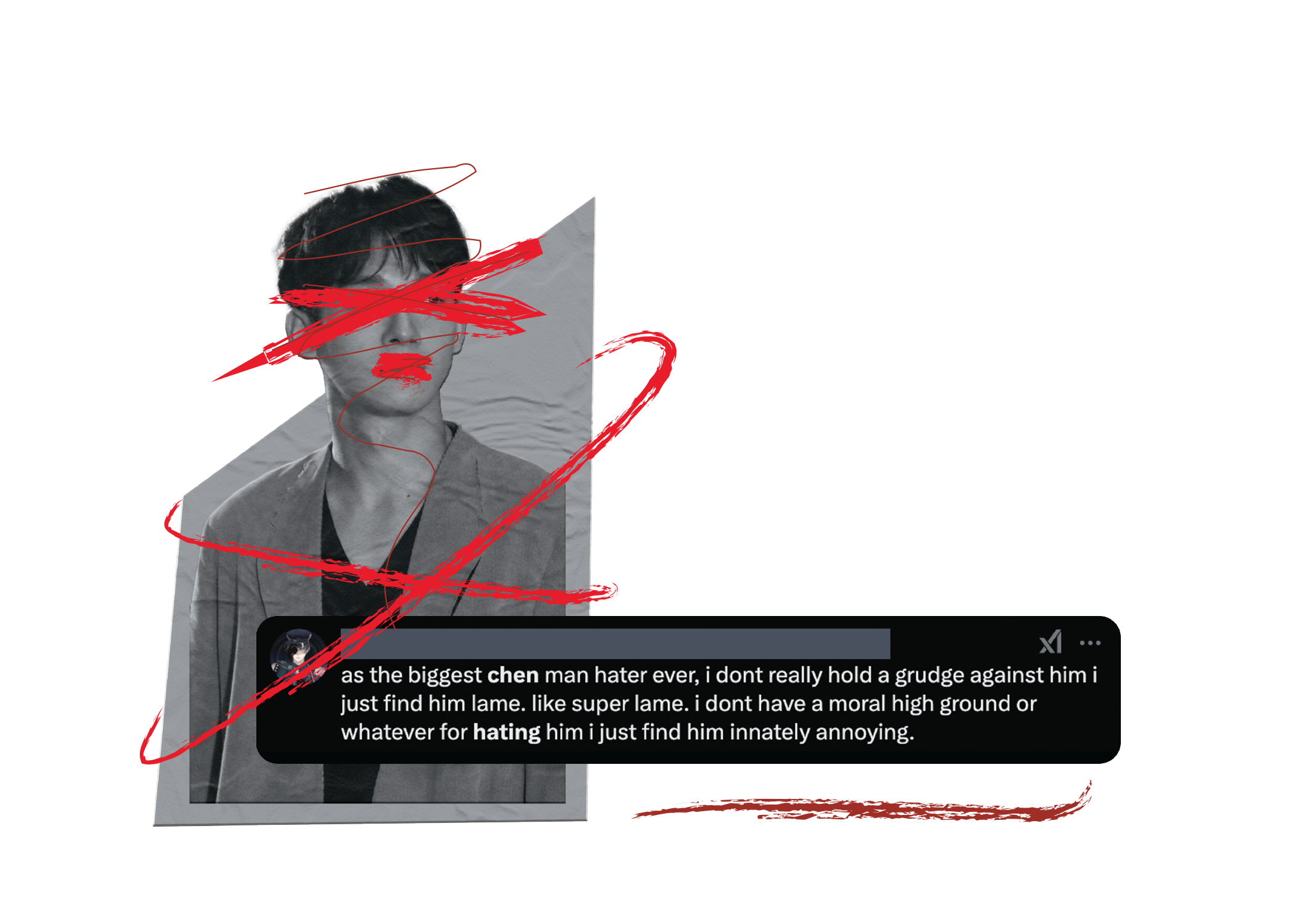

When Chen, a former member of the K-pop boy band EXO, announced his marriage in 2021, Weinberg second-year Yujin Tatar* remembers his fans growing furious online and demanding he leave the group.

Chen’s marriage quickly became major news in South Korea. Reports said fans felt disappointed and disconnected from him because of the announcement. Tatar says she was shocked to see how public figures in South Korea could not have a private life.

“People seem like they feel entitled to have a say in how the idols live their life,” Tatar says. “They’re commodities.”

Cancel culture is prevalent in both Western and Eastern media and can have far-reaching implications, from online and in-person harassment to limited future job opportunities. However, Asian entertainment, especially K-pop, can cultivate an even more intense environment than the West. While it is possible for Western celebrities to continue to appear in movies or release music after getting canceled, Korean idols are more often forced to leave their careers behind or disappear from the public eye altogether. Not everyone can survive the media storm and fan outrage.

“They want the entire celebrity’s life to be catered towards the fans, and so if they can’t maintain this perfect image, then that’s where the criticism starts to come into play,” McCormick third-year Nayeon Kim says.

With the release of Squid Game’s second season in December 2024, fans saw former K-pop star T.O.P return to the spotlight as Thanos after an eight-year hiatus. In 2017, a South Korean court charged T.O.P for marijuana usage, which is illegal and highly stigmatized in South Korea.

Following the indictment, T.O.P repeatedly expressed how sorry he felt and committed to improving himself before disappearing from the spotlight. This is a common response for many Asian celebrities after getting canceled. Korean stars will issue handwritten public apologies for their actions, then take hiatuses from their public careers ranging from a couple weeks to several years. Giving fans enough time to forget about the scandal, then re-garnering support, is key.

Weinberg first-year Jackie Le says T.O.P managed to recover after his drug scandal because his former K-pop group, Big Bang, retains established influence across the world.

“I think it’d be different if he was a newer idol,” Le says. “He’s very well established. At this point, I think people disapprove or they look down upon it. Maybe they’ll shit talk him. But otherwise, it’s like, ‘Whatever we move on with our day.’”

Kim says from an American perspective, smoking marijuana should not stop a celebrity from continuing their career. She says the Squid Game 2 role served as a good opportunity for T.O.P’s comeback.

“I feel like it was him just being himself and just having fun,” Kim says. “If Squid Game wasn’t so popular internationally, then I feel like Koreans would be a lot more quick to criticize him for playing this role.”

Asian media outlets often scrutinize celebrities for behavior that their Western counterparts deem normal, such as talking about mental health or being a feminist. Despite varying legal statuses, drugs like marijuana are somewhat normalized in America, with references appearing in popular songs, movies and music videos. South Korea and other Asian countries do not tolerate drug use.

In October 2023, Studio XU dropped Lee Sun-kyun, best-known for his role as Mr. Park in the Oscar-winning film Parasite, from the project No Way Out following a police investigation into his alleged use of marijuana and ketamine. Despite denying the claims and never being formally charged, brands pulled his face from advertisements. He disappeared from public view as fans and trolls bashed him online. Soon after, he died by suicide, drawing the world’s attention to the intense cancel culture in Korea.

“It’s just so unfortunate that that’s a rising conclusion that a lot of people in entertainment in Asian media are coming to. Like just because of x, y and z thing that’s very minuscule if we compare it to Western culture, ‘Suicide is the only option for me,’” Le says.

In contrast, Western audiences tend to tolerate — even support — celebrities facing fire for drug use, Kim says. She uses Demi Lovato as an example of an American star known for overdosing and doing drugs in the past who has continued their career.

“In America, I feel like it’s more focused on the recovery and how they get over that addiction,” Kim says. “Meanwhile, in Korea it’s just focusing on the fact that they did it.”

On whether cancel culture is justified or if it’s gone too far, Le says there is a growing sentiment that fans should recognize idols as human beings and allow them to live their lives without constant media control.

“They’re not just this fantasy figure in your brain that you can project yourself onto and whenever you want,” Le says. “They have needs, they have wants and they should be allowed those needs and wants.”

*Tatar previously contributed to nuAZN.