How one rock album mirrors my journey through grief.

by Rahib Taher

‘Suddenly / March the 13th / Papa said goodbye’

Suryakant Sawhney, lead singer of the Delhi-based alternative rock band Peter Cat Recording Co., sings these words on the third track of the band’s latest album, BETA. The song, named “Suddenly,” is Sawhney’s attempt to come to terms with life after his father’s passing.

I first listened to the band in the spring quarter of my freshman year. My introduction was a song called “Memory Box” from their album Bismillah, meaning “in the name of God” in Arabic.

Muslims have developed the practice of saying Bismillah before virtually every action. Bismillah can be an expression of gratitude or a way to anoint yourself with God’s blessing before facing difficulty. It is most commonly said before reciting a chapter of the Qur’an.

My father, a Bengali Muslim, introduced me to the phrase as a part of my religious upbringing. After his death, Bismillah became a way for me to understand this new phase of my life. In the name of God, my father was lifted into the heavens. This was meant to happen — it is the one guarantee of life.

Still, I was so very conflicted. A constant in my life had disappeared. “Suddenly” came to me after a year of wrestling with an inconceivable hole in my soul. Those lyrics chart the course of the life I have lived since he’s been gone and the life I have yet to live.

‘He left this world and the world he loved was in Dubai’

The world my father loved was Bangladesh, where he was born. For the last 20 years, he had been developing an apartment complex to return to and retire in. It was a dream that would not come to fruition. I could not bring him back there in time. Everything happened too quickly.

Truth be told, when I started writing this, I could not remember the specific date of my father’s passing. It was late June 2023, right after the end of my freshman year. I searched for our last messages, the texts I sent while the surgical tubes were the only thing keeping him alive. His body was internally bleeding and his organs were failing, limiting the time I had to communicate something, anything. These were long blue streaks recounting old memories and regrets, promising to do better if only I could have a miracle. I think it was the night of June 27 leading into the morning of the 28th, at around 3 a.m. I vaguely remember the call from the hospital, a moment of wailing as I looked down into the front yard from the balcony, a 15-minute drive and an encounter with reality: my father’s lifeless body.

My father was a smoker. I remember him saying he started when he was 15 years old in Bangladesh. The habit followed him throughout his life, with brief respites of quitting and then relapsing. I grew to love this smell, purposely inhaling it if I caught a whiff. Even when he tried to hide it, disappearing for 30 minutes and coming back into the house, the scent told the truth.

Before he died, he was admitted to Jamaica Hospital Medical Center in Queens. He suffered a heart attack the last time he went off to smoke. Initially, his condition seemed stable, and I wasn’t worried about the consequences. I had seen this scene before.

He had been in and out of hospitals before for complications with his heart. It felt normal to me. We both thought that he could continue to smoke without fatal repercussions.

This time was different. When the doctors removed the machine stabilizing his heart, he was internally bleeding. The doctor did not say he was dying; rather, she kept saying he was “very sick.”

But these words were wedged between contradicting statements — medical observations that made it clear his death was more likely than not. Still, when I heard that phrase, I clung to the hope that he could recover from this “sickness.” I spent the next three days waiting and praying, but his time had come.

The machines plugged into his body that had been keeping him barely alive were all gone. I felt ejected out of my body, almost unconscious. All the Bengali words I knew spilled into his lifeless ears, recounting the experiences we shared and the regrets that lingered. I poured it all out so hard that I vomited into my hands. I can’t remember much of it except for that final release.

‘Can we kiss you? / Before the fire burns you to the bones’

“Suddenly” references Sawhney’s Hindu upbringing. It follows in Hindu funeral tradition that the deceased’s body is cremated. In the Islamic funeral tradition, it is buried in the ground. There is a moment prior, in both traditions, where the body is cleansed and often wrapped in a white cloth.

My father was like that in his casket. When I was younger, his beard was jet-black and trimmed. As the years passed, it grew more, and white hairs sprouted on his chin, blending into a patch. Now, this beard and his face were all that remained uncovered by the sheet.

The sensation of his prickly beard hairs on my fingers and palms was a constant in my life. I took as long as I could before allowing my fingers to kiss the skin and hair on his face, no longer alive with the warmth of blood.

A hearse carried him to a local mosque. Faces of strangers, of family, of anyone who could come followed the casket to the front of the prayer area. I was not ready to be so vulnerable, but I had to say some words, to paint a picture of what he meant to me. It was the story of the afternoons I spent with my father at the Friday prayer.

In the afternoon, we would walk to the masjid for prayer in the congregation. On our way out, he would take money from his wallet, push it into my hand and ask that I put it in the donation box. The meaning of this gesture was double: a way to instill donation, a pillar of Islam, as a habit but also a selfless act. In his stead, I would receive the goodness of his actions.

In my youth, I did as I was told without thinking much of it. My parents did not often directly speak their feelings. It was rare to hear the word “love” on their tongues. This eulogy was the way to let this feeling free, for the message of love to reach me in a different way.

‘Papa I know / You were fighting to live your life your way / Wherever you are / I hope you’re playing’

In the following days, I felt emotions I had never felt before. I began to develop a resentment towards my father. I asked how my mom and I were to continue. I asked how he could leave so easily and carelessly. I asked why he continued to overwork himself and cope with cigarettes. He knew he was eating himself alive but did not do anything about it.

It was not selfish of me to ask. The doctors in his life advised him against everything that led to his death. It was unthinkable to everyone around me that someone who barely turned 50 was so suddenly gone.

I think I have inherited a lot from my father. I have been a procrastinator for as long as I can remember. As I grew older, procrastination turned into avoidance. Avoidance became a lifestyle. It was easier to do nothing and waste my time than face something that would cause me any discomfort.

My father was trying to avoid something within himself that made him deeply miserable. I do not know if I will ever know what that is. All I can know is the cigarette smoke and the excessive time working was an escape worth more to him than his life.

For me, this deeply miserable thing was his death. I spent many weekdays of my childhood home alone while my parents worked into the evening. I did not have much of an opportunity to speak from the heart. All of that makes me want to run like he did.

‘I’m losing you from my mind as I grow older too / Your memories are the only peace, the place I own / These songs I sing are the only way to make you listen’

I became more pious following his death. There are five daily prayers in Islam, from sunrise to sunset. These were opportunities to maintain a connection that was physically unavailable to me. I wanted nothing more than my prayers to reach God and for that to mean something for my father’s place in the afterlife, just as my father put donation money in my palm during the Friday prayer.

As I try to remember him, I always think of a phrase he would repeat: “This life is temporary.” It described his outlook on life, which was just a test for the afterlife. For Muslims, there was joy in death, in a promise of eternal life in heaven.

These words constantly ring in my head and prompt other memories to flow. I recall those days following freshman year when I was in New York City again. Whenever I went out into Manhattan, he would text me so I could let him know if he could pick me up. I miss it so badly.

During one of my freshman year quarters, I was on the Dean’s List. I sent him a screenshot of the email. I think this new distance between us made him yearn for me more than he had ever before.

He said words that had been rare to me and so enthusiastically, too. The text message read, “Congratulations my son. I’m really proud of you. You made my life cherish... joyful... lot more.”

I miss the random ellipses in place of commas, a signature of South Asian fathers.

More than anything, his death enshrined life’s transience. I wasn’t always so religious, but now I feel that neglecting my faith will make my worst fears come true. That one day I will forget his voice, his image, his scent — everything that made him, him.

Islam was so important to him. It is one of the only paths toward him that I have left. The prayer I conduct is the only way to make him listen. It is the only assurance that our souls will encounter one another again in the life after this one.

‘Can we hear you? / Or maybe see a sign that says hello?’

There is a persistent voice in my head that asks why I continue to get up in the morning. I miss my father. I miss the family we were before. I wish we could enjoy one more time together.

I know I have to continue. It is hard, but it is the only thing I can do, to make a future that my parents can be proud of. I have lost so much, but there is still so much time to gain, to heal and to break out of this avoidant pattern. I don’t know what anything looks like ahead, but I will only know if I take a step forward. I have no idea where he is now and if he’s watching over me. But wherever you might be, Dad, I hope you’re playing.

‘Through everything we lost / Your ship has sailed’

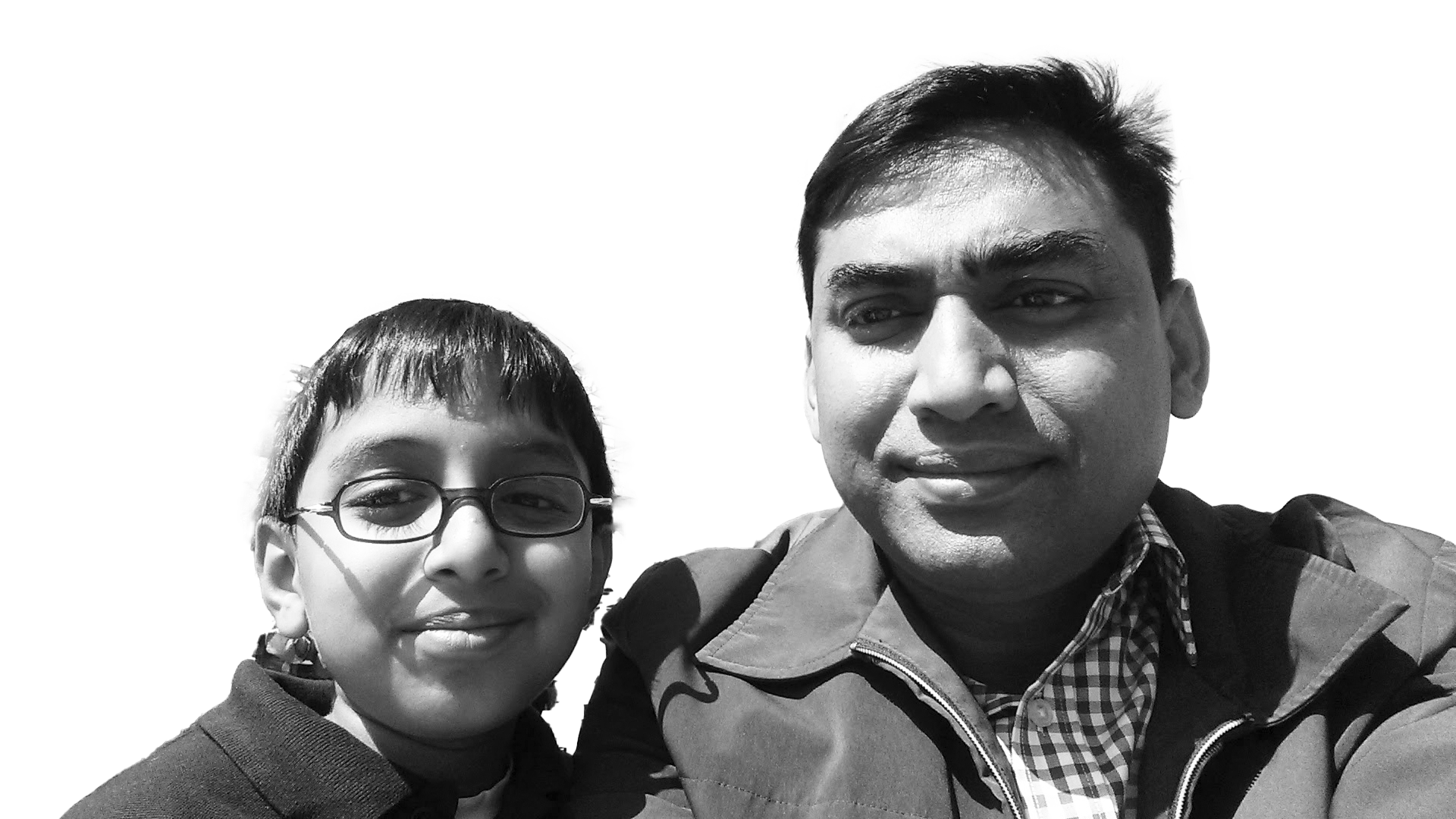

PHOTOS COURTESY OF RAHIB TAHER