Recipe for no reaction

Cooking up allergy-friendly alternatives to traditional food.

by Medina Miranda

It’s Christmas Eve, and my stomach rumbles as I eye my grandmother’s dining table. It’s piled high with traditional Filipino dishes, and steam fills the room as I scoop colorful stews onto my plate and dig in — Mangan na! Let’s eat!

But after one bite, my throat tightens, my skin erupts in hives and my cousins watch in confusion as I wheeze. I glance down at my plate. What looked like chicken was actually shrimp — one of my worst allergens.

Food facilitates cultural connection, but allergies can complicate that relationship. I can’t try the recipes my grandparents depended on when they emigrated to California in the 1970s. I can’t eat ginisang sardinas, my mom’s favorite childhood dish, since it contains fish. Most importantly, I can’t visit my family in the Philippines, since my food allergies are too much cause for concern.

This disconnect isn’t unique to my experience. In the U.S., food allergies and other immune conditions like asthma and eczema disproportionately affect Asian populations, though the reasons remain unclear. A 2021 Johns Hopkins study suggests different environmental factors between Asia and the U.S. may contribute to rising allergy rates. Because of these differences, newer generations might be at higher risk, which could explain why my brother and I have food allergies while our parents don’t.

Asian students at Northwestern are working to raise awareness and maintain connections to their heritage through food. From scientific research to ingredient substitutions, Northwestern’s food allergy community balances advocacy with everyday challenges, seeking both safety and cultural belonging.

Like me, Weinberg fourth-year Sanjana Rajesh has had to navigate food allergies since the age of 4. Developing allergies changed her relationship with South Indian cuisine, both in America and India. Although her immediate family accommodates her dietary restrictions, Rajesh says many South Indian dishes include her allergens, like coconut and egg. As a result, she says food is a point of tension in her family.

“Going to India is really hard because people don’t know that allergies exist,” Rajesh says. “They don’t know how to deal with it.”

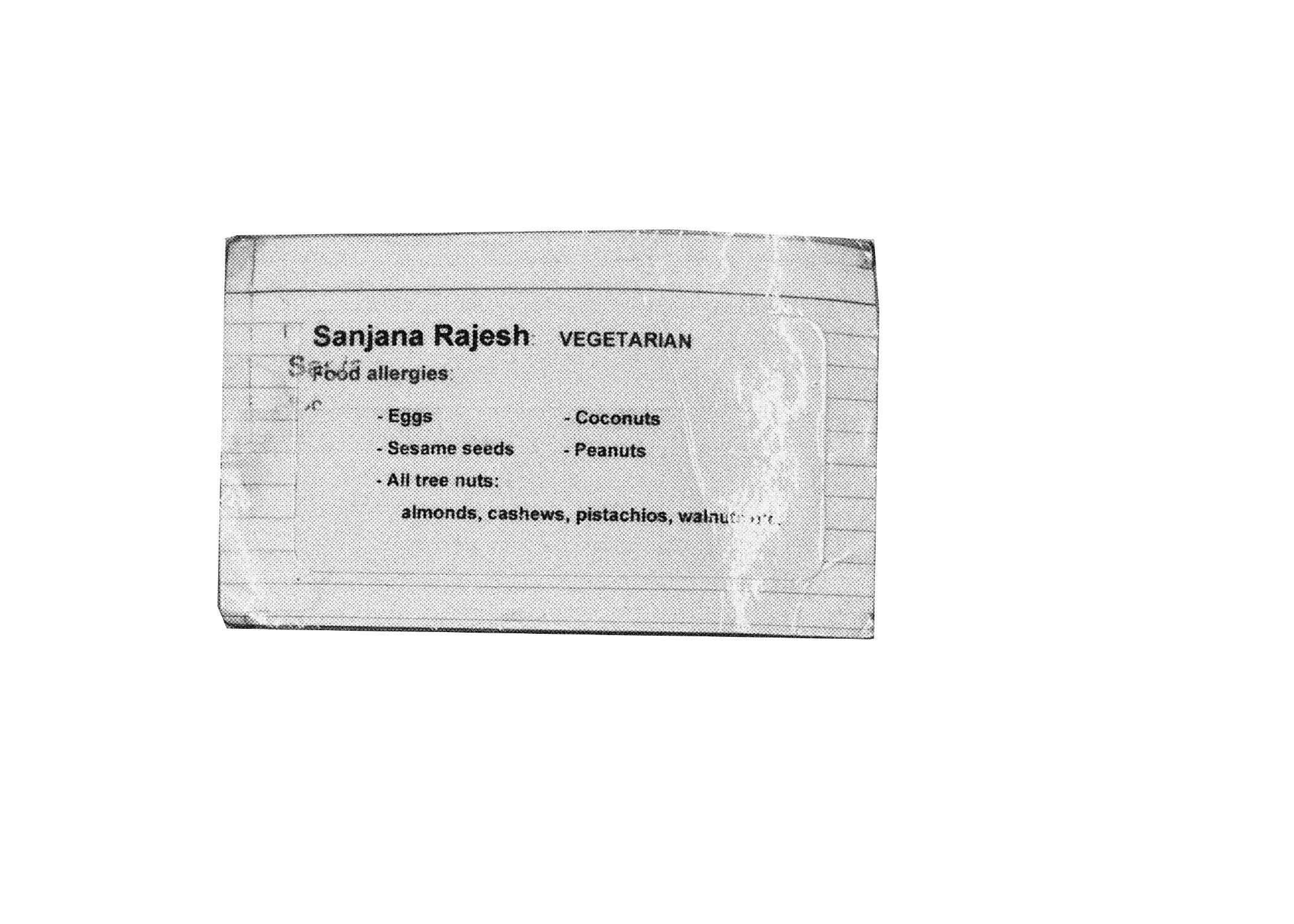

At Northwestern, Rajesh often feels like a “Debbie Downer” when choosing restaurants with friends because she limits their options. But she’s found ways to advocate for herself. She carries allergy identification cards she laminated with packing tape, keeping some in each of her bags.

“It’s nice to hand it to a server,” she says. “I’ve even sent these to friends, because it’s so much easier to have things written out.”

Rajesh has been using the cards since 2021. She also carries both an Auvi-Q and an Epipen, handheld devices ready to administer a life-saving dose of epinephrine — a stimulant that relaxes airway muscles — if needed.

Northwestern offers other food allergy resources for students without these devices. Rajesh receives allergy shots from Northwestern Medicine Student Health Service, and Weinberg third-year Preena Shroff says her close bond with NU’s previous dietitian has helped her feel safer in dining halls.

Off-campus cooking gives students like Shroff and Rajesh the freedom to experiment with different ingredients.

“I can make [food] exactly how I want, even if it doesn’t taste the best,” Rajesh says.

Shroff shows me her Indian spice tray, which she uses as a flavor base to make dishes like muthia, a flour-based dumpling that can be steamed or fried. She appreciates the control that comes with off-campus cooking.

“If I’m cooking, I can make what I want to eat,” she says. “I can also make what everyone else will also enjoy eating.”

Shroff is a student researcher at the Center for Food Allergy and Asthma Research (CFAAR) at Northwestern’s Feinberg School of Medicine. She recently examined 217 colleges’ allergy safety measures, finding that only four schools stock emergency epinephrine in dining halls.

This March, Shroff will present her research at the annual American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology and the World Allergy Organization Joint Congress in San Diego.

“I’m really excited. I’m going to be talking to a lot of healthcare providers and physicians, because the number of people entering college with food allergies is increasing,” Shroff says.

In NU’s chapter of College Advocates for Food Allergy Awareness & Education, Shroff and other NU students have created digital resources to help fellow students adjust to Northwestern and Evanston dining.

Sometimes, having a support system is all it takes for allergies to not feel so burdensome. Sharon Wong, a research associate at CFAAR, started Nut Free Wok, an allergy-friendly Asian recipe blog, after both of her children were diagnosed with severe food allergies over a decade ago. Through a rigorous testing process, she develops practical allergen-free recipes, fine-tuning them using her mother’s sense of taste.

“I ask, ‘What do you think, Mom?’ and if she likes it, then I know it tastes good. And if I’m willing to make it, I know it’s very easy,” Wong says, laughing.

Wong says dim sum dishes like cheung fun, a traditional Chinese steamed rice roll, can be adapted by substituting the traditional shrimp filling for other ingredients. Families tell Wong that her recipes help kids feel included at meals.

“It makes me super, super happy that these kids have this way to eat, enjoy their foods and partake in their family dinners,” Wong says. “They can share the recipes with their aunties and their grandmas.”

Thirteen years have passed since that fateful Christmas Eve, and I’ve learned a lot. Now, I ask my family to swap shrimp for tofu and crab for chicken. I confidently ask wait staff for allergy accommodations. And as I hunt for apartments with my future roommates, we’re excited to stock our kitchen with food we love — and can safely eat.