Affinity attacked

Closing in on diversity, equity and inclusion.

by Edward Simon Cruz

Courtesy of Multicultural Student Affairs

Feinberg Prof. Dr. Minoli Perera found out in early April that the National Institutes of Health was terminating one of her research grants due to diversity, equity and inclusion concerns — part of how the federal government has been erasing DEI initiatives.

But scientifically, she says diversity is key to her work, contrary to the Trump administration’s attempts to claim otherwise.

“This is sort of a co-opting of the idea of ‘diversity is bad,’ but in most of science, diversity is actually the thing we are,” Perera says.

Since President Donald Trump took office a second time and introduced policies to roll back DEI initiatives in education, Northwestern has clamped down on its own diversity policies, including by removing references to them on all of its schools’ websites. NU and its Multicultural Student Affairs’ website temporarily redirected visitors to a page saying the University was “reviewing its policies and programs to ensure we meet all federal and state laws and requirements.” These changes came as the Department of Education warned universities in a mid-February letter that they would lose federal funding if they failed to remove programs that treat students differently based on their race.

As the Trump administration continues its crackdown on DEI and the University reevaluates its support for DEI initiatives, faculty and students worry about losing future funding for research projects as well as University support for affinity spaces and ethnic studies programs. Such losses would make it harder for scholars to support future research and for students to build community.

Humans share about 99.9% of their genes with each other, and Perera’s research examines differences in the remaining 0.1% of people’s genes — also known as genetic diversity — to explore how people of different ancestries respond to certain drugs or medications. Previous research on drug responses focused largely on people with European ancestry, but those findings became less helpful when applied on people with different ancestral backgrounds.

Perera’s research focuses on Hispanic people and people with African ancestry, and she says discoveries from genomes in those populations have informed recommendations for choosing and dosing current medications given the overall genomic similarities among all humans. At the same time, she adds that Hispanic and African-ancestry people contain genetic variations not present in European populations, making research into diverse populations valuable and necessary.

“Relabeling broadly diversity as something that is not what we want in science is actually antithetical to genomic medicine, because genomic medicine relies on diversity in the genome,” Perera says.

But researchers nationwide have already faced cuts in their funding if their research is connected to any aspect of DEI. On top of the Trump administration freezing $790 million in federal funding for NU, various federal agencies have revoked research project grants in recent months, with the potential for additional cuts looming. The NIH and National Science Foundation have terminated at least 20 grants to various research projects, including Perera’s work and several projects addressing LGBTQ+ health.

Even the threat of losing funding has dissuaded some scholars. Anthropology and Asian American studies Prof. Shalini Shankar, for example, started drafting a research proposal about South Asian Americans in Silicon Valley for a fellowship under the National Endowment for the Humanities. But with the Trump administration repeatedly revoking grants for research projects tied to race or ethnicity, she opted not to apply.

The project would have followed up on her ongoing work exploring how India’s caste system promotes socioeconomic and linguistic inequality in the United States.

“I was well-positioned to do this research,” Shankar says. “But now it’s questionable — both how I will get it funded as well as who will want to talk to me in this current environment, where everyone fears the repercussions of making statements about things that fall under the DEI heading.”

Some professors do not conduct federally funded research, but they have still felt the effects of Trump’s threats against universities. Prof. Nitasha Tamar Sharma directs the Asian American Studies Program, which she says has already exhausted its annual budget for the first time in her six years at its helm. It’s now harder to book guest speakers, field trips and similar events, she says.

Sharma took five seniors to the Association for Asian American Studies conference in April. During a panel discussion about the students’ research, Sharma asked them about their plans for the summer. None of the students had definitive answers. And this year, unlike in previous years, Sharma did not encourage the seniors she taught to attend graduate school, even though they would have been qualified.

“We’re going to have a whole generation of people who are not going to graduate school, which means they’re not going to become professors or researchers,” Sharma says. “What does that mean for the future?”

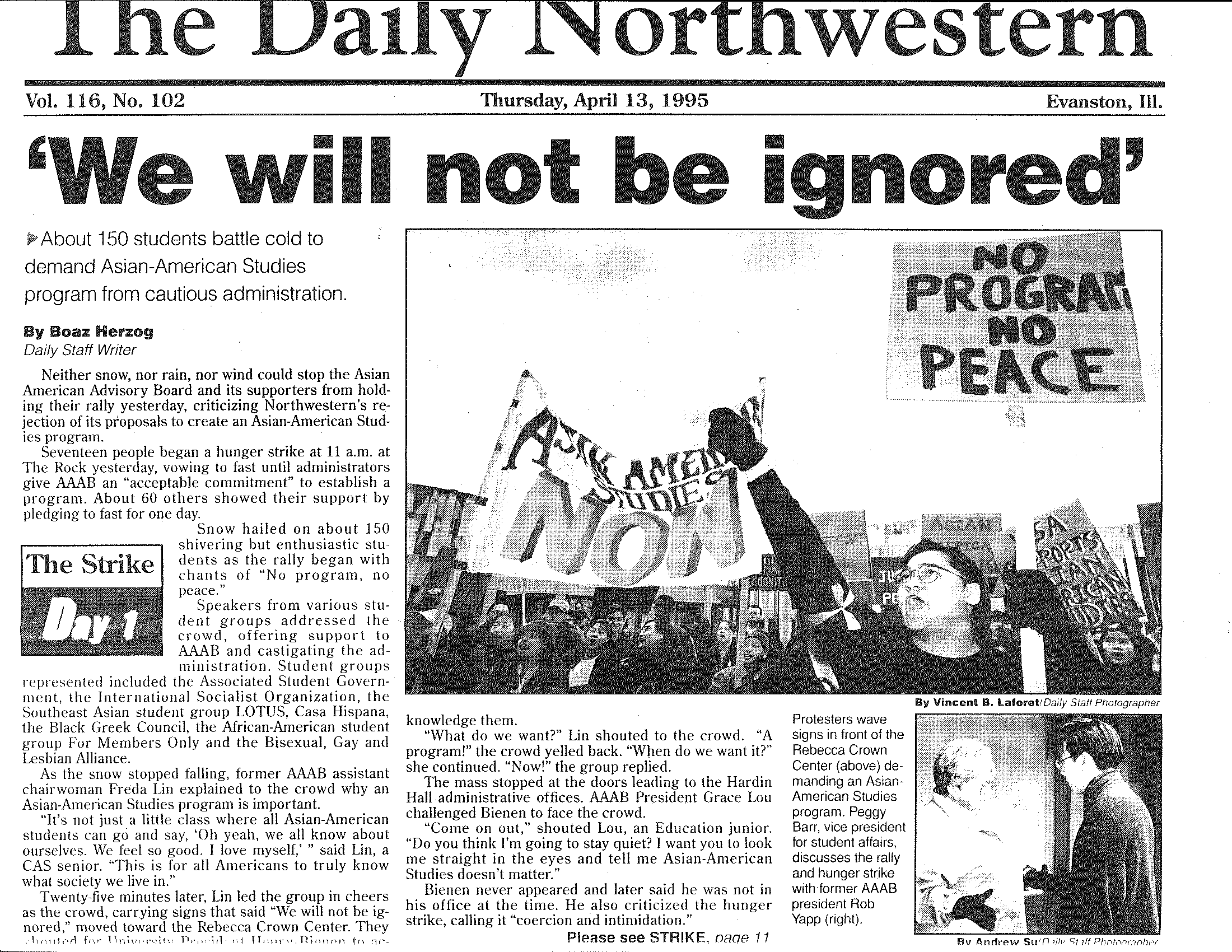

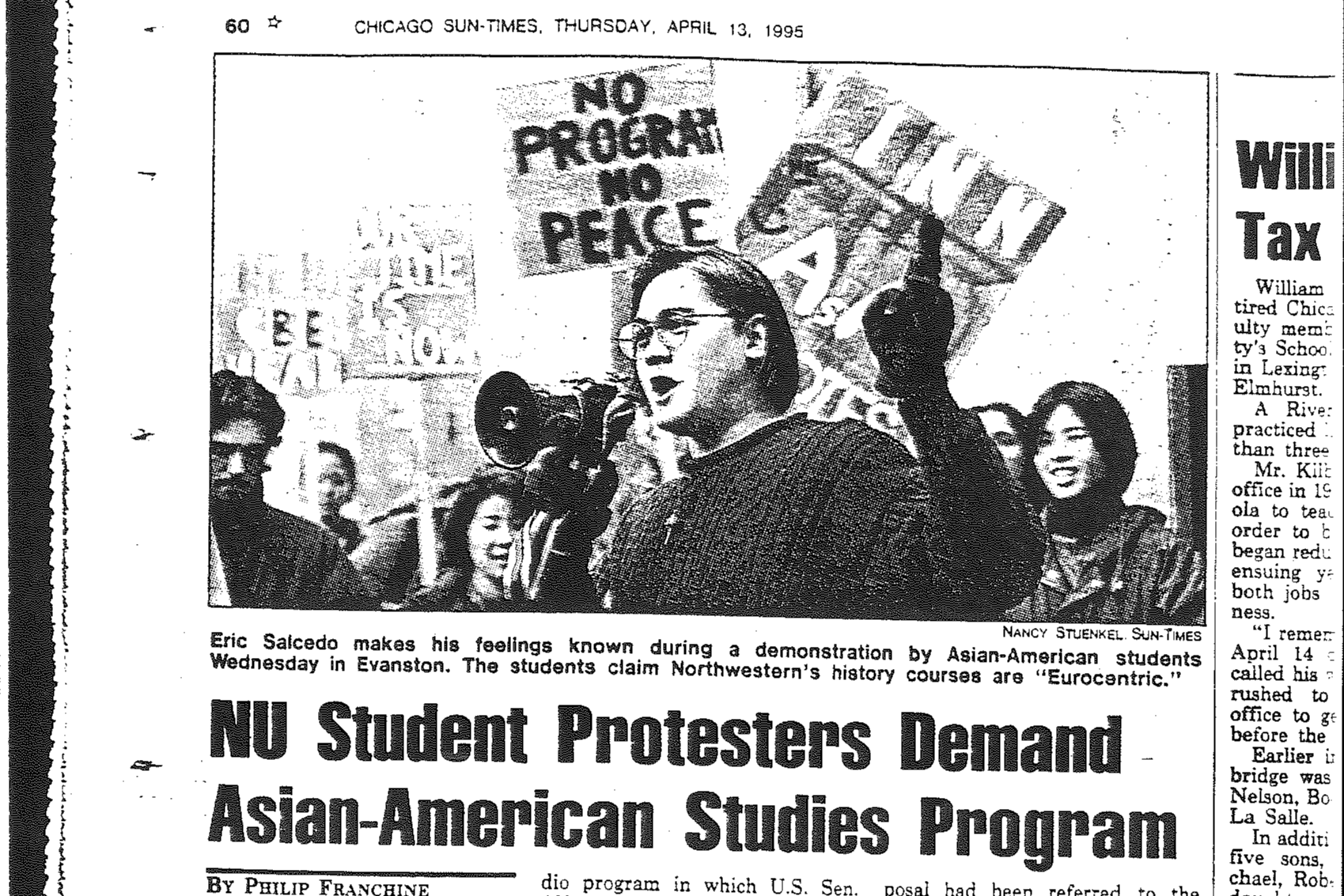

Like other ethnic studies programs around the country, NU’s Asian American Studies Program emerged from student activism. In 1995, members of the school’s Asian American Advisory Board — the precursor to today’s Asian Pacific American Coalition, or APAC — joined other students in a 23-day hunger strike to demand the University establish an Asian American studies program. It took four more years for the University to create an Asian American studies minor.

While NU’s website for Asian American studies displays this record of activism, APAC co-president and SESP third-year Jade Chi says Multicultural Student Affairs staff has been told to “sanitize” its language, speaking about its broader mission without specifically discussing historical protests led by non-white students.

The original MSA website returned online in mid-April, and on April 24, a federal court blocked the Department of Education from enforcing the demands in its February letter. MSA still promotes events on Instagram, though Weinberg fourth-year Jinhee Heo and other students say they rely on “peer-to-peer communication” more than before.

In a May 1 post advertising events for Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month, each event’s description contains a disclaimer that “all are welcome to attend.” Federal guidance from February instructed educational institutions to not deny students the ability to fully participate in school life, regardless of race.

Chi says APAC is mostly proceeding as normal with its events, such as hosting a May 7 dialogue titled “Migration and Citizenship Under Empire.” However, the group remains concerned about potentially losing support from MSA. One of the MSA’s assistant directors serves as an adviser for multiple student groups, including APAC, and APAC hosts many of its events in the Multicultural Center.

Heo, who’s worked for MSA since her first year at NU, says the Multicultural Center provides a valuable space “staffed by students and mostly inhabited by students” for her to discuss sensitive political topics with her peers, as well as feelings of exclusion or dissatisfaction with the University.

Heo says spaces supposedly designed for “all students” can feel alienating to those from historically marginalized groups. Many of those students can feel like an “anomaly” in the larger student culture of the university, pressuring them to behave differently to fit in with professors and peers outside their chosen community. For her, the Multicultural Center provides a sense of security that can’t easily be replicated elsewhere.

“Trust in a new location is built over time,” Heo says. “I think assuming that the same communities would be able to rebuild in the library or somewhere off campus — I think that would be a false assumption.”

Several students and professors also say affinity-based end-of-year celebrations may not return in their previous formats. The University will allow students to wear identity-based stoles or their caps at commencement ceremonies, Heo says, but will not place it on them during commencement or while walking the stage. It only reversed a previous plan to ban those stoles following student backlash. Shankar says she has heard from colleagues and students that the University received requests from Black and Latine students interested in maintaining affinity-based ceremonies, but not from Asian American students.

Shankar says she found it “bizarre” that administrators would wait to hear students request the affinity-based ceremonies themselves. She knows multiple students of Asian descent who want such an event.

“If you’re preserving some of those ceremonies, why wouldn’t you offer that just automatically to all of these minoritized students?” she says. “Because if they wanted to have a ceremony like this before Trump took office, nothing will have changed.”

University spokespeople did not respond to questions about funding cuts, support for non-citizen students and faculty, academic freedom or identity-based commencement.

Sharma says she has repeatedly asked Weinberg Dean Adrian Randolph if the University plans to close the Asian American Studies Program. She says others in the room would laugh in response, as if the proposition were ridiculous.

But Sharma warns that closure remains possible — universities across the country have shuttered ethnic programs and departments. The University of Toledo announced in late April that it would suspend majors in Africana, Asian, Disability, Middle East and Women’s and Gender Studies. That came after Columbia University launched a review into various programs studying the Middle East and Harvard University fired the leaders of its Center for Middle Eastern Studies.

With many ethnic studies courses exploring interplays between issues like race, colonialism and capitalism, Sharma says she and other professors display a “double consciousness,” recognizing they may be reported or reprimanded at any point for their teaching.

University President Michael Schill reiterated the school’s commitment to “academic freedom” in separate emails from March 6 and May 1, though Sharma criticized NU for adopting the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance’s working definition of antisemitism in alignment with Trump’s executive orders. That definition names “the targeting of the state of Israel, conceived as a Jewish collectivity” as a form of hate against Jewish people.

“Without a doubt, the line that the deans and higher administration said would not be crossed, which was about academic freedom, has already been crossed,” Sharma says. “We are very cautious and affected by that in ethnic studies.”

With students becoming angry and disillusioned at University administrators, Weinberg fourth-year Roy Zhu says more of them have begun organizing. They cite teach-ins during the National Day of Action for Higher Education on April 17 as well as a May Day event led by Students Organizing for Labor Rights.

However, the University instituted new demonstration policies in September after public scrutiny of the University’s handling of pro-Palestinian protests on campus. Amid these changes — as well as immigration authorities detaining college students associated with pro-Palestinian protests — Zhu says some students have expressed discomfort about participating in meetings or demonstrations with groups like Students for Justice in Palestine. They say this “fear” about potential legal consequences has stymied some efforts at sustained organizing.

“Things have certainly gotten worse, but fear is not a productive place to work from as an organizer,” Zhu says.

Chi says cross-hosted events between affinity groups strengthens their sense of community. APAC and other student groups are collaborating to send a joint statement to the University administration condemning its compliance with the Trump administration.

Alongside other student leaders, Chi says these interpersonal connections would be even more important if NU administration began reducing support for affinity-based student organizations. Chi notes previous campus movements in which students across racial backgrounds came together: Black and Latine students joined the 1995 hunger strike petitioning for AASP’s creation, and Black, Latine and Asian students came together in 2018 to demand the departmentalization of various ethnic and gender studies programs at NU.

“There’s a history of solidarity that we’re trying to build on, and we’re not as fragmented as we might seem to some people,” she says.

Sharma is part of the University Under Threat collective, a group of faculty members organizing educational events about federal policy changes and advocating for NU administrators to stand up to the Trump administration. Sharma says these movements must extend beyond identity-based affinity groups given the history of systemic oppression against different marginalized groups.

“Ethnic studies can teach us more broadly about how these systems were developed,” Sharma says. “But it will only change what we’re going through if we link those different oppressions.”