Heritage of my own

Identities overlap for Asian adoptees.

by Janelle Mella

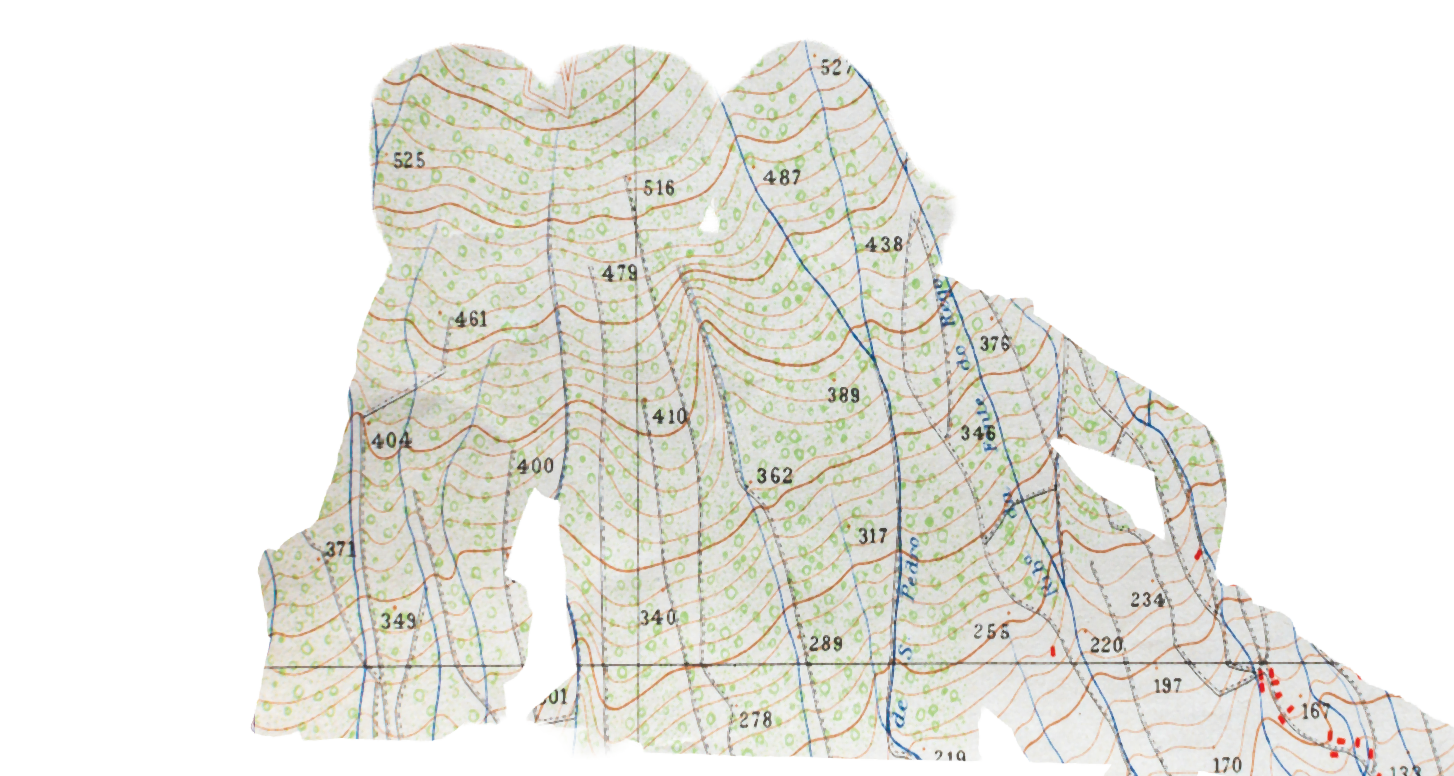

Courtesy of Lynne Romanelli

Courtesy of Maeve McAuley

When Weinberg first-year Maeve McAuley was in high school, she wanted to join a club that pitched itself as a space for anyone who feels “stuck between two worlds,” a description that resonated with her as a Korean American adoptee raised by Irish parents.

“‘Hey, could I join? I know I’m not multiracial, but I feel multiethnic, and I have that tension between what I am or what I should be,’” McAuley says she told the president of the club. “She fully told me no.”

McAuley, like many Asian adoptees raised by white families, often struggled to fit neatly under a single ethnic label. As they grow older, many adoptees navigate the nuances of their adoptive family’s culture alongside an unfamiliar Asian heritage, sometimes feeling disconnected and often reconnecting with parts of their identity they hadn’t before.

Growing up, McAuley says her parents were very accepting of her and her adopted younger brother, immersing them in Irish culture. As a result, she says she often feels “more Irish before feeling Korean.”

“The assumption is that because I look fully Asian, I will be accepted in that community,” McAuley says. “But because I don’t understand any of the language or have zero spice tolerance to follow, I really have no clue where I am when I do enter that space.”

McAuley says she has never been to Asia and says she is still learning about aspects of her culture, such as trying Asian food, discovering how they vary across cultures and figuring out what she likes. She describes this exploration of her Asian heritage as an ongoing journey.

While McAuley’s upbringing was shaped by Irish traditions, other adoptees grew up with a blend of cultural influences. For Weinberg second-year Lynne Romanelli, who was adopted from China when she was 1, that blend always felt normal.

Romanelli was raised in a predominantly white neighborhood in suburban Michigan by a white father and a Filipino mother. At home, her family celebrated Chinese New Year and “Gotcha Day,” often with Chinese food and watching home videos from her parents’ trip to China to pick her up. She grew up alongside two adopted siblings — an older sister from China and an older brother from the Philippines.

Those celebrations always felt normal to Romanelli because she had cultural traditions to share with her adopted siblings.

However, other adoptees with parents of different races say they feel a disconnect from their Asian culture at times. Communication third-year Andre Pang, who was adopted in China by an Irish immigrant mother and Chinese American father, felt this rift, noting there were times they often struggled with feeling not fully Chinese.

“I would compare myself to the other Asian-presenting students in my school,” Pang says. “I’d be like, ‘They’re smart, they have good grades, they eat this for lunch, they do this, they do that. I don’t do that. Why don’t I do that? What’s wrong with me?’”

They were often insecure about their Chinese language skills and would compare themself to their classmates, recalling one moment when someone said, “Andre’s Chinese sucks” — a comment that hurt deeply, Pang says.

Pang also felt a disconnect when they expected people to judge them and their mother for not looking alike, something that lingered in their mind and made them feel self-conscious about how others perceived them. They felt more drawn toward exploring their Chinese culture, which felt less accessible in their environment, partly because they often spent summers in Ireland with their mother but never got the chance to visit China after being adopted, Pang says.

This sense of cultural disconnect growing up is something SESP third-year Emma Manley also experienced as a Chinese adoptee. Raised by her Irish and English parents in predominantly white communities, Manley sometimes felt distant from her Asian heritage.

“Even if I wasn’t actively thinking about it, it would be pointed out to me,” Manley says, noting that it was always clear to her that she was adopted and people would mention how she didn’t look like her parents.

When she got to high school, Manley says she and her best friend, who was also adopted, often gravitated toward spaces with other students of color. Their conversations centered more on navigating school and identity in a predominantly white environment than on cultural traditions or heritage.

As these adoptees grew older and arrived at Northwestern, some like Weinberg first-year Jillian Suarez, found new ways to explore their Asian backgrounds.

Suarez, a Chinese adoptee raised by two white parents, says coming to Northwestern was a “big shift” from her high school experience, finding herself surrounded by more people who shared her Asian heritage. She realized how much she still wants to learn about her culture.

“At Northwestern, since you pull from a lot of other areas where there’s more diversity, it’s a lot more of an environment that I fit in with,” Suarez says. “There’s more opportunities, more people with similar interests.”

Though she admits she knows little about Chinese language or traditions, she’s formed friendships with people who have helped bridge that gap by teaching her Chinese words and sharing insights on food, like picking out Chinese restaurants for them to go to together.

Pang extended their efforts to connect with their Asian culture beyond campus during a study abroad trip to Taiwan, where they took Chinese language classes and made friends with international students. They described those moments as opportunities to reconnect with a culture they “left.”

“I wasn’t raised in a Chinese household, which is both a blessing and not a blessing in certain ways,” Pang says. “It means that I’ve tried to find this and connect with this by choice, and that’s been a fulfilling adventure.”

Despite these opportunities, some adoptees still find it difficult to fit under the umbrella of being an adoptee in college.

When Manley first arrived at NU, a Wildcat Welcome group event asked that students stand up if they resonated with particular identity descriptors. She says there was a question asking if students had ever been in foster care or were adopted, and she stood up — along with only a few other students.

It was an awful experience, according to Manley, being among so many of her peers and being one of the only people standing. She says she and others left the event crying.

This feeling of not quite fitting in didn’t stop there. The disconnect Manley faced in high school followed her to Northwestern, where she considered attending information sessions for multicultural sororities but decided against it, partly because she felt out of place, she says.

“I definitely considered it and I almost went to a couple, but I always had trouble because I was like, ‘I feel too culturally white for this,’” Manley says.

For some adoptees, the cultural identity they seek to understand isn’t tied to their Asian heritage at all, but instead comes from the families that raised them.

Weinberg third-year Peter Burleson, adopted from China and raised by white parents in Texas, didn’t think much about being adopted until his late teenage years. When he did, his curiosity led him to enjoy learning more about his family’s history — not his biological roots, but the stories and traditions of the people who raised him.

“I’ve really made it an important point to know about my family’s history, just because I feel like that’s an important thing, even though it’s not necessarily something I’m blood-related to,” Burleson says.

As some adoptees find a sense of belonging through exploring their heritage or connecting with others who share similar experiences, others are still figuring out where, or even if, they want to fit in at all.

For McAuley, being adopted isn’t always about aligning perfectly with a single identity. Through her experiences, McAuley has learned to embrace multiple sides of her identity.

“What was most helpful for me was just the excitement of it all and realizing that being adopted doesn’t mean you’re one thing or the other,” McAuley says. “It means you’re both, and that’s a really cool thing to be.”

Courtesy of Jillian Suarez

“I feel too in-between to be in this space, and I don’t think I will feel like I connect.”